-

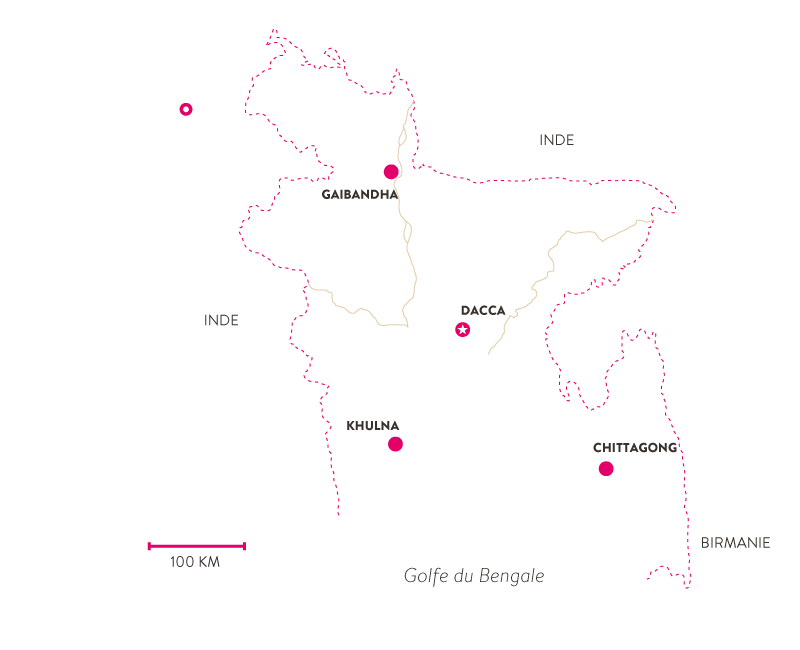

Bangladesh

Bangladesh, Under an emancipating sun

Bangladesh is one of the countries most affcted by climate change and also one of the poorest in the world. To provide access to electricity – at last – to the millions of Bangladeshis living in rural areas, in 2003 the World Bank and the State set up a rural electrifiation programme using solar energy, which has been a resounding success. Some 3.7 million individual photovoltaic systems have already been installed. Next target: 6 million by 2018.

Bangladesh is one of the countries most affcted by climate change and also one of the poorest in the world. To provide access to electricity – at last – to the millions of Bangladeshis living in rural areas, in 2003 the World Bank and the State set up a rural electrifiation programme using solar energy, which has been a resounding success. Some 3.7 million individual photovoltaic systems have already been installed. Next target: 6 million by 2018.The appearance of electric light alone has transformed the lives of these families. Women can cook in the evening and have time free in the daytime to work, and little girls can do their homework, and delay the age at which they marry.

Writer: Cécile Bontron | Photographer: Laurent Weyl

Thanks to electricity, Sheili can cook in the evening. During the day, she spends a couple of

hours selling solar panels. She earns commission which is paid into an account in her sole name.

Narayanpur Chor (Island) on the Jamuna (brahmapoutra) river in the Kamarjani region, northern Bangladesh.

Among the twists and turns of the Ganges and Brahmaputra river delta and amidst the chars coming and going with the rises in water levels from the monsoon, it is very difficult to build an electricity network. The reasonably flexible technology of solar panels constitutes the best solution for providing electricity to these isolated areas.

This is the biggest electrifiation program in the world. There are some trials in Africa and South America, but nothing on the scale seen here.”

Zubair Sadeque, energy expert at the World Bank in BangladeshVery active in climate change research

Situated on the largest delta in the world, the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta, Bangladesh is feeling the full force of the consequences of climate change. Rise in sea level and river levels, ever more numerous and more devastating cyclones … Climate change has become an unavoidable issue in the search for development.

At the beginning of the 2000s, Dr Atiq Rahman, co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize with the IPCC (the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), launched a long experiment to bring electricity to an entire island thanks to photovoltaic sensors. The prelude to the individual solar panel programme. «We would never have believed it would be such a success!» admits Atiq Rahman.

It’s very hard to study without electricity. With the kerosene lamp, I would always fall asleep. It’s light is not strong enough. Today (thanks to the solar panels), I can study much longer: 4, 5, 6 hours.”

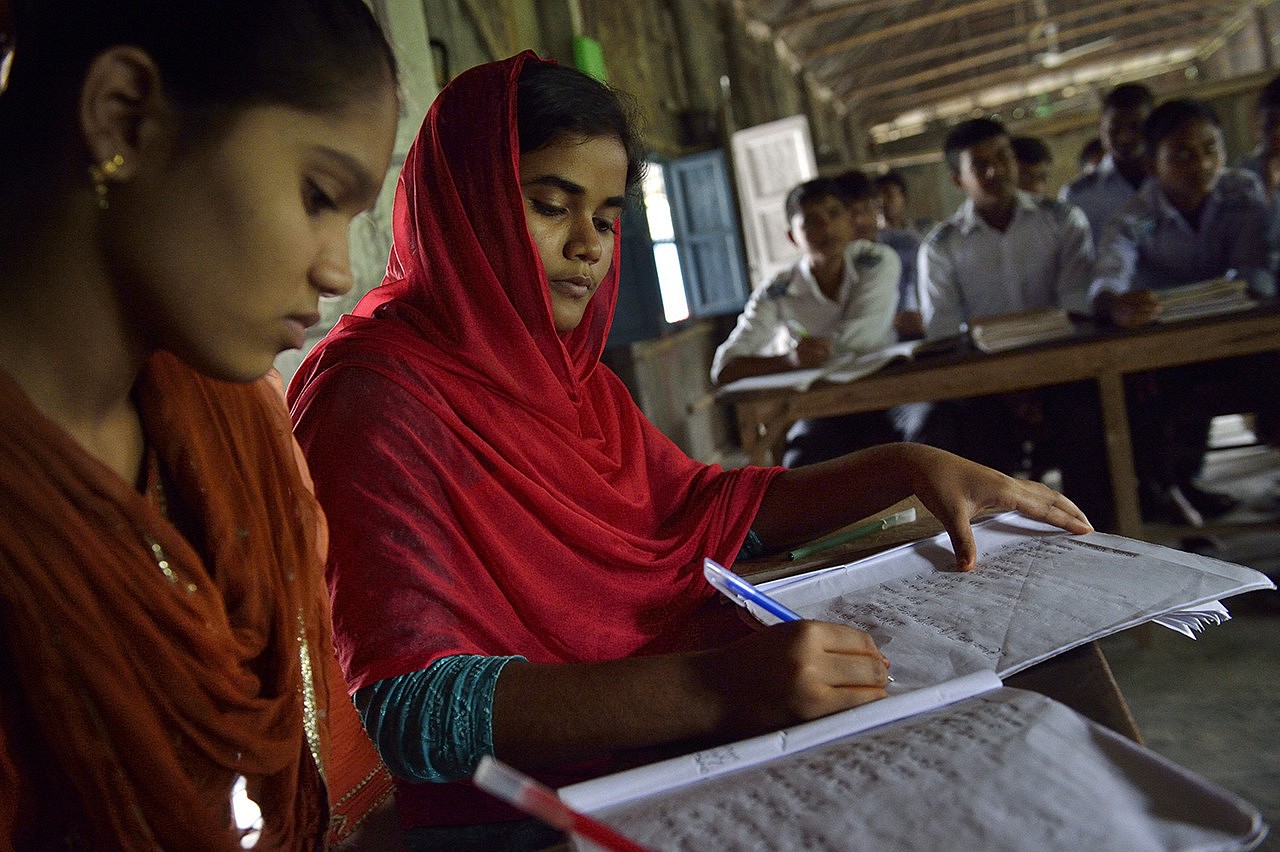

Shathi, 14 years old, student of Kamarjani school in Korai Bari.Rajia Sultana is studying to put off marriage

Mosammat Rajia Sultana was born fourteen years ago on the banks of the Brahmaputra, in one of the «mushroom» quarters of a small port, Korai Bari. As her father has lost his mind, her mother has to make ends meet with the small rent the family fild brings in and the help of her wider family. Impossible to buy a solar panel, even a small one.

But thanks to her good school results, Rajia Sultana has won one, a 20 watt model. The girl, with her dark eyes and determined look, long hair carefully knotted under a long scarf, has taken advantage of the electric light to spend more time on her homework: between four and fie hours every evening so that she get into university. Her uncle, acting head of the family, has promised her that he will not marry her offas long as she is still studying. Her mother was married at the age of twelve.

Emancipation of women

In what is still a very traditionalist country, where women in rural areas have no horizons other than the home, the massive arrival of solar panels enables NGOs to develop female working, at least for a few hours a day. Assembling or repairing parts, or even selling solar panels, enables tens of thousand of women to gain a little independence whilst continuing to play their role as stay-at-home mothers.

The light produced by electricity offers better conditions for children to do their homework in the evening. And for the little girls, it changes everything: more and more families agree in postponing the forced wedding after the girls finish their studies.

Large networks all over the country

The success of the scheme relies to a large extent on microfiance. It was in Bangladesh that another Nobel Peace Prize winner, Muhammad Yunus, created the Grameen Bank, the fist institution to generalise microcredit, loans for very small amounts granted to people normally excluded from conventional banking.

Bangladesh has become the cradle of a multitude of microfiance institutions that are well established all over the country. The individual solar panel program, in which $600 million have been invested since 2003, has relied on these institutions to a very large extent. Forty-six partner associations sell and install the panels and collect the families’ reimbursements every month over two or three years. The pre-existing networks and the legitimacy that these microfiance organisations enjoy with rural populations enabled the scheme to take root immediately.

Today, 65% of the population has access to electricity, including 10% thanks to photovoltaic systems.

Seven years ago, a third of our students quit school before grade 10. Today, we don’t have any one quitting.”

Islam Farukul, director of the Kamarjani school, in Korai Bari.