-

Indonesia

The sugar palm,

saviour of the tropical forests?

Writer: Guillaume Jan | Photographer: Guillaume Collanges

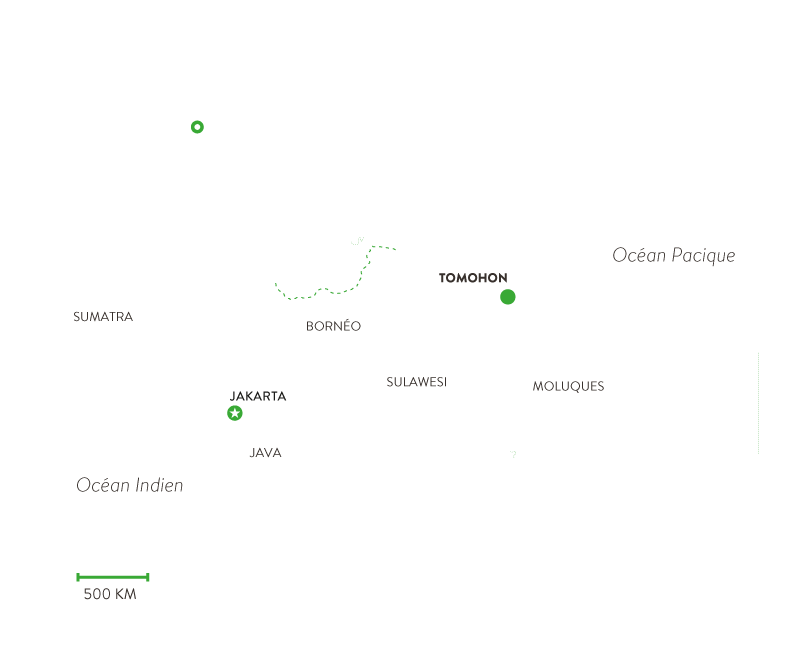

Writer: Guillaume Jan | Photographer: Guillaume CollangesIn Indonesia the Arenga pinnata is a blessing. This sugar palm offers indigenous people an opportunity to earn a living from the jungle without resorting to deforestation. In Tomohon, in the north of the island of Sulawesi, a small factory uses the heat in the volcanic ground to evaporate the sap from this tree and convert it into sugar. Producing no waste and 100% sustainable, this pilot operation will soon be duplicated in several regions of the Indonesian archipelago and could be an alternative to deforestation on other continents.

Hope is returning to this region that was once ecologically damaged

- Stedy Moningka, aren palm sugar harvester on the island of Sulawesi

Unlike the oil palm, whose monocropping is devastating a large part of the Indonesian jungle, the sugar palm prospers alongside other varieties of trees, which provide it with shade. This makes it an excellent ally for the preservation or reconstitution of the forests.”

Record deforestation

Although Indonesia has the third largest tropical forest on the planet, after Brazil and the Democratic Republic of Congo, the country is now world champion in deforestation. Over the period 2000-2012, over 60,000 km2 of jungle were razed, mainly due to the activities of the paper pulp industry, the trade in precious woods and above all the development of oil palm plantations, with Indonesia now the largest producer of palm oil in the world. Not only is deforestation considerably reducing biodiversity on this archipelago of 17,000 islands, but it is also accelerating the discharge of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at an alarming rate. Land clearance, in particular by burning off the vegetation, has made Indonesia the world’s third largest emitter of greenhouse gases, after China and the United States. Thanks to its carbon emissions, Indonesia is therefore the third biggest contributor to climate destabilisation.

Rural inhabitants are grouping together in cooperatives to fight against deforestation

A home-made and ecological exploitation

The aren palm tree produces up to 50 litres of sugar sap a day (or about 7kg of powdered sugar, after transformation). This magical tree provides the farmers that work it with a comfortable income all year round, without damaging the ecological balance of the forest. In Tomohon, in the north of the island of Sulawesi, Dutch biologist Willie Smits introduced a development plan to reforest the hills stripped bare by farmers over the last few decades. He then encouraged the sugar sap harvesters to work together. Finally, using geothermal energy, easily accessible on this volcanic island, he developed a prototype factory capable of transforming the sap into sugar without generating any waste or CO2. He has therefore created a circular economy that is enabling the region to develop in a harmonious and sustainable way.

The farmers’ work requires good knowledge of the jungle, as well as strength and endurance. Jusuf Wungow, 63, is the Elder of the Masarang cooperative.

- Jusuf Wungow, aren palm sugar harvester on the island of Sulawesi

In environmental terms, our working together in this way has immense advantages. Instead of burning 3 or 4m3 of wood a day to transform my harvest into sugar, I use the cooling circuit of the geothermal plant as a collective asset that I share with the other harvesters. This means we are saving about 20,000 trees a year.”

Production that respects nature and is good for the environment

There was an urgent need to change habits. Deforestation was so extensive that the rainwater was no longer being filtered by the vegetation. Every year, in January and February, Tomohon was suffering spectacular floods. Paradoxically, the springs were drying up as the trees vanished, we were dying of thirst.

And the climate was becoming hotter and drier outside of these periods of flooding. In 2005, a first team of villagers began planting trees. By 2010, 230 hectares of forest had already been reconstituted. Since then, reforestation has continued.”

Julius Pontoh, professor of sciences at Sam Ratulangi University in Manado